Polish Lower Secondary School Teachers and Headmasters in the Light of Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS 2013)

- Published on Tuesday, 29 July 2014 14:58

Work with pupils with special educational needs, classroom management, use of modern technologies – these are the main training needs of Polish teachers. 94% of Polish teachers believe that it is necessary to focus on teaching children independent thinking. Polish teachers are distinguished by better discipline during classes. Only in Poland teachers are appraised solely by headmasters.

.Educational Research Institute published the results of the Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2013. This is the second cycle of the survey organized by OECD. The study enables comparison of teachers’ opinions and information about their work and their impact on the learning process of pupils.

More Women Headmasters in Poland

An average lower secondary school teacher in the countries participating in the TALIS study is 43 years’ old. In Poland, an average teacher is one year younger and has an average professional experience of 17 years. An average teacher works in a small public school. Around the world, the teaching profession is dominated by women. However, the higher the educational stage, the fewer women occupy managerial positions. In Poland, the percentage of women headmasters in primary schools is 72%; in middle schools - 67%, whereas in post-secondary schools - 53%. Headmasters are usually people aged 56 – 66; the percentage of headmasters in this age group in comparison to 2008 rose from 29% to 49%.

Polish teachers and headmasters have better formal education than their counterparts in many other countries; 99% of them are university graduates. University training for teaching profession seems common in the examined countries. The exception is Flanders (Belgium), where 85% of teachers prepare for work at schools in higher vocational schools.

Polish Teachers Not Very Old, But Not Very Young Either

Ageing of teachers constitutes a significant problem for educational systems of certain countries: Italy (the average age is 49 years, and 50% of teachers are over 50) and in Estonia (48 years) in particular. Compared to 2008, this problem is visibly aggravating particularly rapidly in Italy, Portugal and Bulgaria. Even though in Poland the ageing of teachers is currently not a problem, a small percentage of young people in teaching is conspicuous.

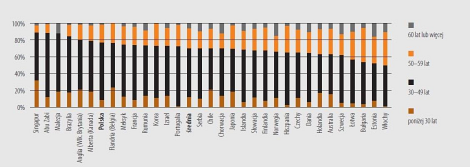

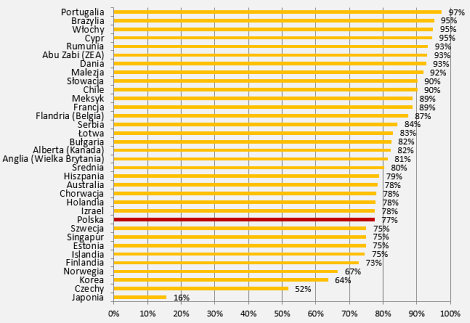

Percentage of teachers grouped by age in TALIS countries

[60 years’ old or older; 50 – 59 years’ old; 30 – 49 years’ old; below 30;

Singapore, Abu Dhabi, Malaysia, Brazil, England (Great Britain), Alberta (Canada), Poland, Flanders (Belgium), Mexico, France, Romania, Korea, Israel, Portugal, average, Serbia, Chile, Croatia, Japan, Iceland, Slovakia, Finland, Norway, Spain, Czech Republic, Denmark, Holland, Austrialia, Sweden, Latvia, Bulgaria, Estonia, Italy] Percentage of teachers grouped by age in TALIS countries

Percentage of teachers grouped by age in TALIS countries

Evaluated Less Frequently and Only by Headmasters

In contrast to other countries participating in the survey, all teachers are evaluated in Poland. However, the evaluations are performed quite rarely and only by headmasters.

In other countries, various people take part in the process of evaluation, e.g. other teachers, members of the school management team (including parents), designated supervisors or external persons and institutions, e.g. local authorities. In Poland, 93% of teachers declare that formal evaluation, as well as provision of informal feedback is done by headmasters (in comparison to TALIS average of 54%).

In Poland, formal evaluation of teachers’ work is carried out relatively rarely – over half of Polish teachers received work evaluation once every two years or even less frequently.Work of 70% of teachers in Malaysia and 62% of teachers in Romania is evaluated by their headmasters twice or more often in the course of a year, and in the majority of European countries – once a year (in France – 82%, in Germany – 60%, Norway – 64%, Sweden – 59%, England – 53%, Finland – 50%).

In Poland, the following aspects are subject to evaluation: pupils’ work (91%), class management (87%) and competences related to the teaching of a specific subject (86%). According to teachers, evaluation of their work has no formal consequences in practice (e.g. in the form of bonuses, wage raises, termination of employment).

Polish Teachers Know What Training They Need

One of the greatest needs of Polish teachers in professional improvement are skills and knowledge useful in working with pupils with special needs. In Poland, almost twice as many teachers as in other TALIS countries (58% and 26%, respectively) work with such pupils. This may testify to better awareness of this phenomenon, but also to broader scope of the definition of special needs in Poland.

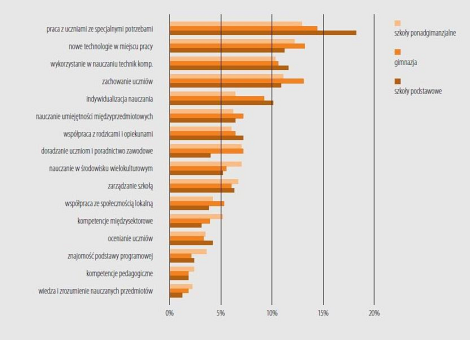

The needs for professional improvement voiced by the teachers primarily refer to work with pupils with special educational needs, with class and use of new technologies in the work place.

Teachers’ needs for professional development: percentage of Polish teachers declaring high level of needs Teachers’ needs for professional development: percentage of Polish teachers declaring high level of needs

Teachers’ needs for professional development: percentage of Polish teachers declaring high level of needs

• teaching students with special needs;

• new technologies in the work place;

• use of computers in teaching;

• student behaviour and classroom management;

• individualized teaching;

• teaching cross-curricular skills;

• cooperation with parents and guardians;

• student career guidance and counselling;

• teaching in a multicultural setting;

• school management;

• cooperation with local community;

• cross-occupational competencies;

• student assessment;

• familiarity with the core curriculum;

• pedagogical competences;

• knowledge and understanding of the subject ¬field(s)

[secondary schools; lower secondary schools; primary schools]

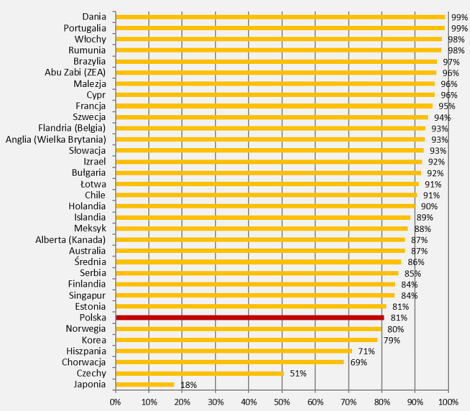

Lower secondary school teachers’ needs for professional development in comparison to their counterparts in TALIS

Lower secondary school teachers’ needs for professional development in comparison to their counterparts in TALIS

Lower secondary school teachers’ needs for professional development in comparison to their counterparts in TALIS

• teaching students with special needs;

• new technologies in the work place;

• student behaviour and classroom management;

• use of computers in teaching;

• individualized teaching;

• student career guidance and counselling;

• teaching cross-curricular skills;

• school management and administration;

• teaching in a multicultural setting;

• cross-occupational competencies;

• student assessment;

• familiarity with the core curriculum;

• pedagogical competencies in the specific teacher field(s);

• knowledge and understanding of the subject ¬field(s);

[Poland; average]

In Poland, the percentage of teachers participating in various forms of professional development increased (from 90% to 94%); teachers mainly choose training programmes in subject-specific knowledge, pedagogical competencies, work with pupils with special needs, assessment and curriculum. However, the view the benefits of such classes critically; their impact on their manner of teaching was described as “moderate”, by 44% - 58% respondents, depending on the area.

Polish Teachers Better at Behaviour Management than Students’ Support

An overwhelming majority of teachers believe that drawing conclusions and reasoning rather than acquisition of specific knowledge are most important. As many as 94% of Polish teachers believe that in the process of teaching, it is necessary to allow students to solve tasks independently, whereas the role of the teacher consists in facilitating students’ own investigations.

However, they use activating methods such as work in small groups (42%) or longer projects (16%) less frequently than teachers from other countries.

Polish teachers, when asked about efficient solving of problems and whether they are able to arouse students’ interest and provide support, and whether they vary the forms of their classes – score worse than their colleagues from other countries.

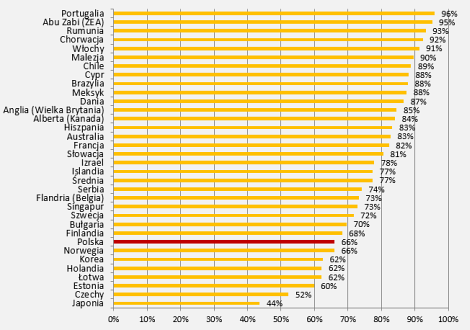

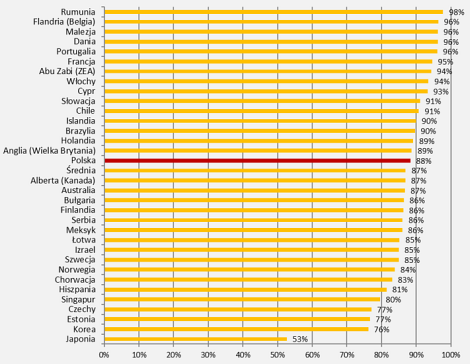

To what a degree in your teaching practice are you able to ...

implement alternative instructional strategies in my classroom Implementing alternative instructional strategies in classroom

Implementing alternative instructional strategies in classroom

[Portugal, Abu Dhabi (UAE), Romania, Croatia, Italy, Malaysia, Chile, Cyprus, Brazil, Mexico, Denmark, England (Great Britain), Alberta (Canada), Spain, Australia, France, Slovakia, Israel, Ireland, Average, Serbia, Flanders (Belgium), Singapore, Sweden, Bulgaria, Finland, Poland, Norway, Korea, Holland, Latvia, Estonia, Czech Republic, Japan]

In comparison to teachers from other countries, Polish teachers preceive more critically their efficacy in instruction and motivating pupils and teaching critical thinking.

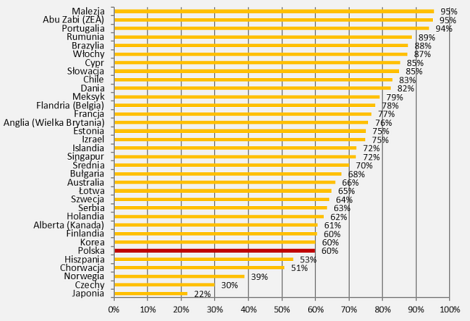

Motivating students who show low interest in school work

Motivating students who show low interest in school work

Motivating students who show low interest in school work

[motivating students who show low interest in school work;

Malaysia; Abu Dhabi (UAE), Portugal, Romania, Brazil, Italy, Cyprus, Slovakia, Chile, Denmark, Mexico, Flanders (Belgium), France, England (Great Britain), Estonia, Israel, Iceland, Singapore, average, Bulgaria, Australia, Latvia, Sweden, Serbia, Holland, Alberta (Canada), Finland, Korea, Poland, Spain, Croatia, Norway, Czech Republic, Japan]

Help students in critical thinking

Help students in critical thinking

Help students in critical thinking

[help students in critical thinking;

Portugal, Brazil, Italy, Cyprus, Romania, Abu Dhabi (UAE), Denmark, Malaysia, Sweden, Chile, Mexico, France, Flanders (Belgium), Serbia, Latvia, Bulgaria, Alberta (Canada), England (Great Britain), average, Spain, Australia, Croatia, Holland, Israel, Poland, Sweden, Singapore, Estonia, Iceland, Finland, Norway, Korea, Czech Republic, Japan]

Get students to believe they can do well in school work

Get students to believe they can do well in school work

Get students to believe they can do well in school work

[get students to believe they can do well in school work;

Denmark, Portugal, Italy, Romania, Brazil, Abu Dhabi (UAE), Malaysia, Cyprus, France, Sweden, Flanders (Belgium), England (Great Britain), Slovakia, Israel, Bulgaria, Latvia, Chile, Holland, Iceland, Mexico, Alberta (Canada), Australia, average, Serbia, Finland, Singapore, Estonia, Poland, Norway, Korea, Spain, Croatia, Czech Republic, Japan]

Polish teachers are less interested in students’ well-being than teachers from other countries and they show less interest in what pupils have to say. They evaluate their efficacy in maintaining discipline in the class better (88%) and they devote least time to managing class behaviour among teachers in other countries (8%; TALIS average: 13%).

To what a degree in your teaching practice are you able to ...

control disruptive behaviour in the classroom

Control disruptive behaviour in the classroom

Control disruptive behaviour in the classroom

[control disruptive behaviour in the classroom;

Romania, Flanders (Belgium), Malaysia, Denmark, Portugal, France, Abu Dhabi (UAE), Italy, Cyprus, Slovakia, Chile, Iceland, Brazil, Holland, England (Great Britain), Poland, average, Alberta (Canada), Australia, Bulgaria, Finland, Serbia, Mexico, Latvia, Israel, Sweden, Norway, Croatia, Spain, Singapore, Czech Republic, Estonia, Korea, Japan]

Polish Teachers Like Their Work

In general, Polish lower secondary school teachers are satisfied with their work; the results indicate that they derive more satisfaction from work at school in which they teach than from practicing the profession as such.

As many as 90% of teachers agree or strongly agree with the statement that they like working in their school; 85% would recommend it as a good work place, and only 17% agree or strongly agree with the statement that they would like to change the school if it was possible. Teachers are also satisfied with the quality of their work – as indicated by 93% of the surveyed lower secondary school teachers giving a positive answer to that question. Differences in comparison to the international average are visible only in question about the potential change of school in which they work – the international average in this case is 21%.

In spite of the satisfaction with their work, over 2/3 of teachers indicate being overloaded with work, uncertainty of employment, low prestige of the profession as most serious problems; four in five teachers are unsatisfied with their salary.

Who Was Examined and How?

The survey covered over 170,000 teachers from 34 countries and regions around the world. In Poland, teachers of general subjects and vocational subjects working at primary schools, lower-secondary schools and secondary schools for children and youth took part in the survey. In total, over 10,000 teachers, over 500 headmasters, including 3,858 teachers and 195 headmasters in lower secondary schools. Random selection of schools for the survey makes conclusions about situation of all schools in the countries and regions participating in the study valid.

TALIS 2013 survey in Poland, similarly to the prior one, was coordinated by the Educational Research Institute. Decisions regarding participation in the study were made by the governments of participating countries – in the case of Poland by the Ministry of National Education; the Ministry also partially financed the survey. On the international level, the project was implemented and coordinated by the Data Processing and Research Center (DPC) at the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, whereas the Secretariat of OECD and the Council Managing the TALIS Programme were responsible for the TALIS survey.

Complete report of the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS 2013) is available at the Internet site of Education Enthusiasts: www.eduentuzjasci.pl